Personal Animus

After a four hour hearing on January 8, Judge H. Thomas Padrick granted a motion to disqualify the Albemarle County Commonwealth's Attorney's office in the case against Jacob Dix. The case will now be tried by a special prosecutor.

Dix was arrested in July of 2023 on a felony charge of burning an object with the intent to intimidate for his participation in the August 11, 2017 torch march at the University of Virginia. His case is one of ten filed against the torch marchers, four of which have already ended in guilty pleas. His defense attorney, Peter Frazier, has been the most aggressive in bogging the case down with motions, seemingly based on spurious legal theories provided by Unite the Right organizer Jason Kessler. Judge Padrick's decision on Monday was a surprising success for Frazier that will likely encourage Dix's remaining codefendants to join in the strategy of substituting conspiracy theory, bluster, and potential defamation for sound argument.

The motion to disqualify the prosecutor was filed in October, but the hearing was delayed by the need to appoint a substitute judge. In 33 pages, Frazier spins a narrative of political persecution, with both state actors and militant activists conspiring to deprive his client of his constitutional rights. It's also riddled with factual inaccuracies, uncited claims, spelling errors, and apparently deliberate misunderstandings of the statute. The primary argument is that the Assistant Commonwealth's Attorney prosecuting the case, Lawton Tufts, has a conflict of interest that requires his removal from the case.

A line by line refutation of the factual misrepresentations in the motion should be unnecessary. Judge Padrick said in his ruling that he felt the Commonwealth's Attorney's Office had acted in good faith, that no actual conflict of interest had been created, and that no specific animus against the defendant was shown. He was instead concerned about appearance - that the evidence presented could potentially create for the outside observer the appearance of impropriety. And while appearance of impropriety is the standard for judicial recusal in Virginia, something he would be familiar with as a judge, the same legal standard does not apply in motions to disqualify a prosecutor. Judge Padrick himself said twice during the hearing that in his decades on the bench, he'd heard many motions to disqualify opposing counsel in civil cases, but had never heard, or even heard of, a case where a motion to disqualify the prosecutor's office was contested.

The failure of the Commonwealth's Attorney's Office to file a written opposition to the motion may have been the deciding factor in Monday's ruling. Judge Padrick entered the hearing having read only the defense motion's presentation of alleged facts, with no rebuttal or countervailing caselaw. If the Commonwealth were to appeal the ruling, they could draw directly from a case cited heavily in the defense motion. The case, Lux v Commonwealth, did result in the Virginia Court of Appeals reversing a lower court ruling on the grounds that the prosecutor in that particular case should have been disqualified, but the opinion spells out quite clearly that actual, rather than possible or apparent, conflict is the bar:

"While we agree that an ethical rule that strives to avoid the appearance of impropriety is a worthy standard for professional conduct, a criminal defendant's constitutional right to due process does not entitle him to a prosecution free of such appearances."

Lux v Commonwealth 24 Va. App. 561

A year after Lux was decided, the same court cited that opinion in Allen v Commonwealth, expanding on the idea:

However, the Commonwealth's attorney must be free to perform his or her prosecutorial duties, unless restrained by actual impropriety or prejudice, or by a substantial risk thereof.

Allen v Commonwealth

With mere appearance being insufficient grounds to remove the prosecutor from a case, the actual allegations presented should be examined. The foundational claims of Frazier's argument - that Tufts "personally helped lead, organize and advocate for counter-protestors" and that he "attended Unite the Right as a counter-protestor" are hysterical exaggerations. Were they true as stated, the conflict of interest would be undeniable - this would be an egregious violation of the right to a fair trial. But, as affirmed in the 2004 Supreme Court of Virginia decision in Powell v Commonwealth, "the burden is on the party seeking disqualification of the prosecutor to present evidence establishing the existence of disqualifying bias or prejudice." In place of that evidence, Frazier offered insinuation and loose association.

Based on a handful of emails produced in response to a Freedom of Information Act request to the University of Virginia, Frazier constructed a theory that the Assistant Commonwealth's Attorney Lawton Tufts had been deeply involved in organizing and participating in counter protest activities during the summer of 2017. When the conspiratorial commentary and falsehoods are stripped away and the facts are placed in context, the 'smoking gun' of personal vengeance from an unethical prosecutor is reduced to a handful of fairly ordinary acts performed by a public servant, albeit under sometimes extraordinary circumstances.

In 2017, Lawton Tufts was employed by the University of Virginia School of Law in the Public Service Center. With experience as a public defender, he provided career counseling to law students interested in entering public service after graduation. In his off hours, he also served on two city government boards whose members are appointed by the city council - the Charlottesville Albemarle Regional Jail Board and a now-defunct body called the Citizen's Police Advisory Panel. Unlike Charlottesville's Police Civilian Review Board formed in the years since, the Police Advisory Panel had no authority to investigate complaints. It was formed in 2008 under Mayor Dave Norris who described the panel's role as more of a community-police liaison, “a bridge between the police department and the community.” Tufts was, as Judge Padrick summarized at Monday's hearing, "a good citizen."

Anne Coughlin is a tenured professor at the University of Virginia School of Law, teaching courses in criminal investigation and feminist jurisprudence. Through her affiliation with the law school's Program in Law and Public Service, she also provides career counseling and mentorship for law students considering a career in public service. In 2017, she was asked by Mayor Mike Signer, her former law student, to participate in Welcoming Greater Charlottesville, a local chapter of a national nonprofit called Welcoming America that works to make communities more welcoming for immigrants and minority groups.

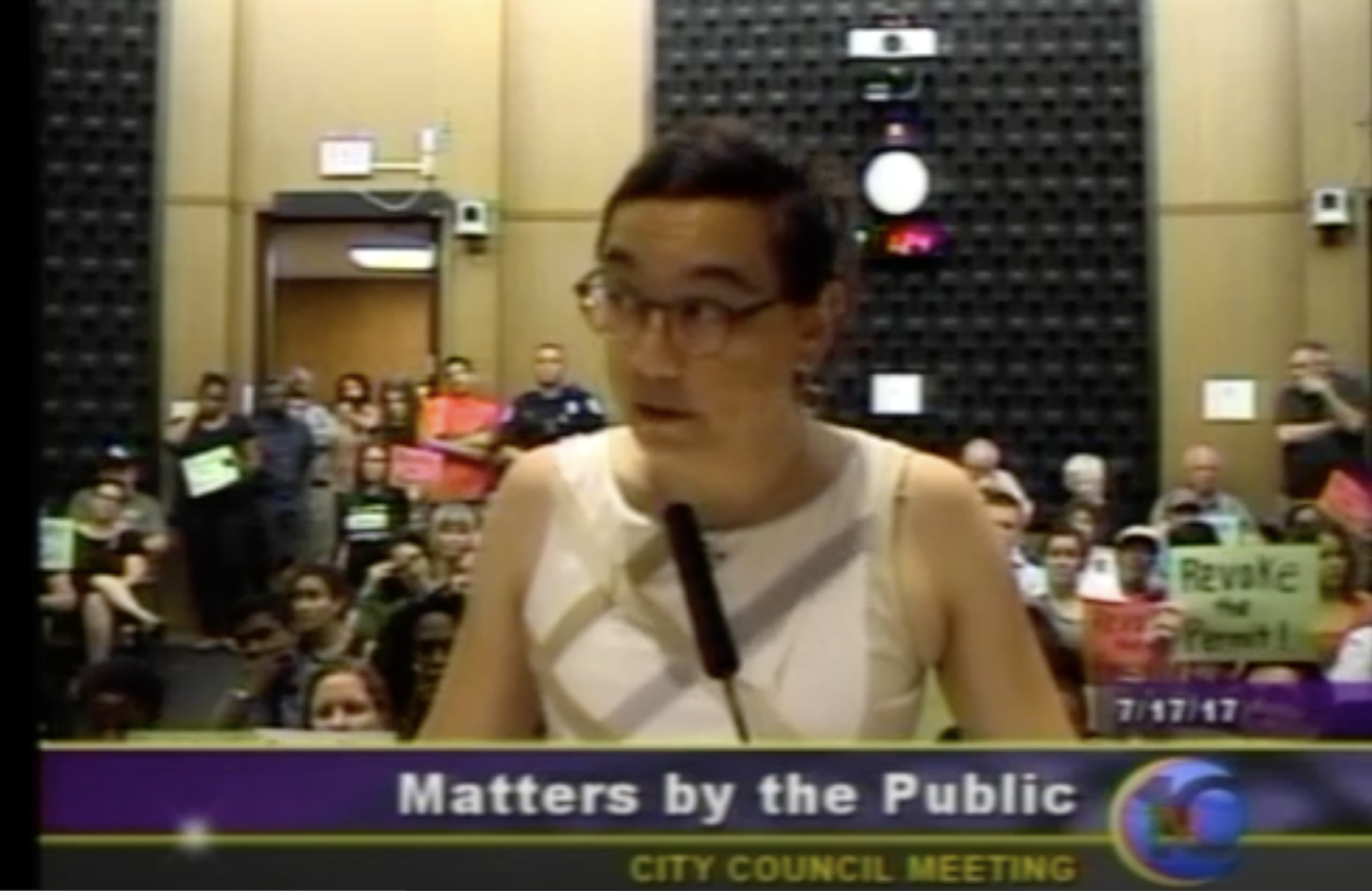

In July of 2017, many residents in Charlottesville were outraged by the police response to the Ku Klux Klan rally downtown on July 8 and feared the upcoming Unite the Right rally on August 12 would be far worse. The organizers of the rally had been working for months to bring together elements of the extreme right at a small park downtown. Some of those planning spaces, like their discord server, had been infiltrated, giving a frightening preview of what attendees intended. Others, like the Facebook event page, showed publicly posted calls for violence. At a July 17, 2017 City Council meeting, Emily Gorcenski presented evidence of some of these threats to council, including threats to members of council's own safety. At that meeting, City Manager Maurice Jones again stated the city's position: they could not revoke the rally's permit, but they could "investigate concerns about threats" and "assess the concerns about that."

In the days after that council meeting, worry about the possibility of violence at the rally grew. With the city's insistence that the permit could not be revoked, some in the community hoped to convince the city to, at the very least, modify the permit to prohibit firearms. Anti-racist activists were not convinced their concerns would be taken seriously and were not comfortable meeting directly with the police in the wake of the police handling of the counterprotest at the KKK rally just weeks earlier. As the emails in Frazier's motion show, activists got in touch with people they thought could help them get their message to the city - Anne Coughlin, whose opinion the mayor respected deeply, and Lawton Tufts, a member of the board meant to help communicate the community's concerns to the police department.

The emails in Frazier's motion span a period of several days, July 27-August 1, 2017. Far from proving that Tufts was "an integral part of this coordinated network" of activists, they show that an appointed member of the City of Charlottesville's Police Advisory Panel, tasked by council with facilitating communication between the police and community, exchanged emails with city residents and assisted them in communicating those concerns in a single meeting with city officials at the end of July 2017. Though Tufts takes issue with some of the language used in the after action report prepared by former federal prosecutor Tim Heaphy, that report does confirm a meeting took place at which Coughlin and Tufts spoke to Deputy City Manager Mike Murphy. In the same section, the report effectively debunks Frazier's claim that Tufts "attended Unite the Right as a counter-protestor." In his own testimony, Tufts said the original plan had been that he, as a representative of the Police Advisory Panel, would be inside the police command center to facilitate effective communication with the community about police operations. When this plan was scrapped by the police department, Tufts instead monitored the situation downtown and sent several updates via text message to CPD Lt. Sandridge.

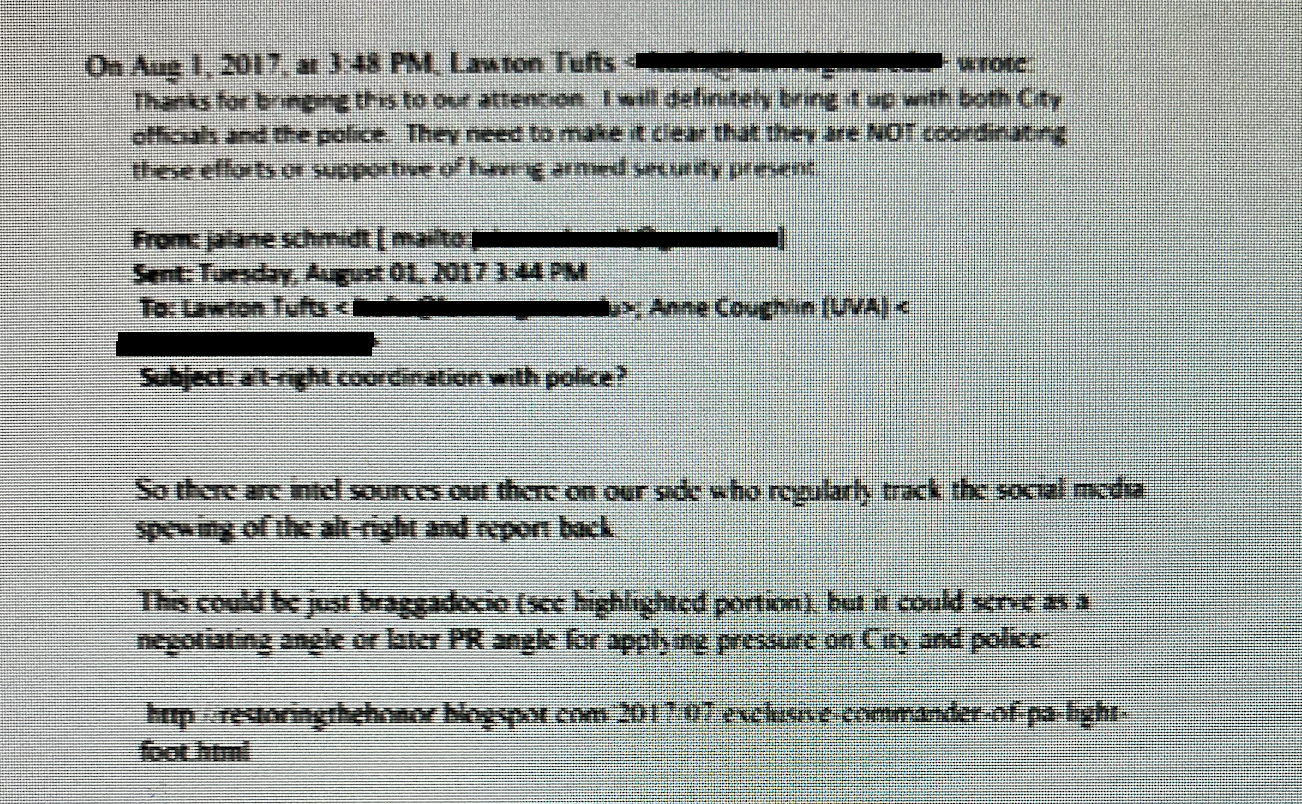

In the final email exchange cited in the motion, dated August 1, 2017, a city resident shares with Tufts a link to a blog post. The post, authored by an activist living in another state, contained a video of a militia leader in Pennsylvania claiming that they were working with local law enforcement to provide private armed security at Unite the Right. With community distrust of the police inflamed after the arrests of anti-racist activists at the Klan rally on July 8, it would be prudent for the department to get out ahead of this claim and clarify for the community that they were not coordinating the efforts of private militias. In his reply, Tufts thanked her for the information and agreed the city and police should provide public clarification.

About twenty minutes after Tufts' reply, the city resident wrote back. News had just broken that the special event insurance policy that Jason Kessler had obtained for the rally had been canceled by the insurance company. She shared a link to the story and suggested that this information could also be shared with city officials as further evidence that the permit should be revoked. Tufts' reply was brief:

My understanding of the legal requirements is that insurance coverage cannot be required for this type of event but I will take a deeper look at it this evening. The insurance provider is definitely smart to cancel!

Frazier cites this email as proof that Tufts formed an attorney-client relationship with Black Lives Matter. While a formal contract or the exchange of payment is not necessary to form an attorney-client relationship, the email does not even show that Tufts' advice was sought nor that he offered a legal opinion. His "understanding of the legal requirements" regarding insurance for permitted events likely came from the very first sentence of the article linked in the email, which states exactly that.

At the time these emails were exchanged, the plan to hold a torchlit rally at the University of Virginia on August 11, 2017 was a closely held secret by the Unite the Right organizers. The entirety of these conversations revolved around the permit issued by the City of Charlottesville for the rally on the 12th, the response by and communication with the Charlottesville Police Department, and decisions to be made by the Charlottesville City Council. At no point prior to August 11 did Tufts or any of these alleged conspirators discuss any detail bearing on this case. They couldn't have. They didn't know. The charged conduct took place on a different date, in a different jurisdiction, under the gaze of a different police department, and without obtaining a permit anyone could have hoped to revoke.

In 1999, avowed white supremacist Paul Warner Powell murdered a teenaged acquaintance after learning she was dating a Black man. After stabbing Stacie Reed in the heart, he waited inside her Manassas, Virginia home for her 14 year old sister to arrive. Powell then raped and stabbed the younger Reed sister, who survived to testify against him. When his original death sentence was overturned because the appeals court ruled the rape of Kristie Reed was a separate crime and could not be used as an aggravating factor in the murder of Stacie Reed, Powell still faced life in prison. From prison, Powell wrote the prosecutor a letter. In that letter, he boasted in graphic detail about the crime, believing that he could not be retried. He was wrong. In a later appeal of his new death sentence, his attorneys argued that the letter was so insulting and obscene that there was no way its recipient had not formed a disqualifying personal animus against the defendant. He argued that his own conduct was so offensive that it would necessarily create such animosity as to render the the target of that behavior incapable of objectivity. The Supreme Court of Virginia disagreed. Making yourself the most hateable man in Virginia does not entitle you to pick your prosecutor, "the evidence must reflect that the prosecutor was acting not within the dictates of the law, but has strayed outside those parameters in furtherance of a personal animus against the defendant."

The facts in Powell aren't a perfect match as a legal argument, but there is a sort of spiritual resonance between those facts and the matter at hand. Jacob Dix is not the first Unite the Right participant to argue that his own conduct, his own beliefs, are so repellant to society as to create an unfair prejudice against him in court, but there's no loophole generated by being detestable. While Powell taunted his prosecutor directly, the creation of animus implied in Dix's case is so dilute as to be homeopathic. There can be no personal animus against Jacob Dix, a man whose name no one in the prosecutor's office knew until the investigation was reopened into the events of August 11.

Something I worry gets lost in this conversation is the time. The 'Summer of Hate' wasn't a single event. History remembers the moment of impact, but fails to capture the dread, the buildup to that day. Charlottesville. Unite the Right. It conjures an image instantly: a snippet of video of men with torches, a photo of twisted metal and blood on the asphalt. I'm not sure how many people remember, or ever knew, that ordinary people tried to prevent it. Black Lives Matter, Showing Up for Racial Justice - these weren't militant, well-funded, highly organized entities. In 2017, in Charlottesville, these were ordinary people. They were our neighbors, friends, and coworkers. They were grandmas and pastors and college students. They were people who met at church or walked their dogs together or saw each other in the school drop off line every morning. Some people saw what was coming and they tried to raise the alarm. They used the tools at their disposal to try to keep each other safe. The city failed them. The courts failed them. The rally was not cancelled. And we all know the rest.

But without that context, without the boring parts of the story where people debated the finer points of the municipal code regarding special events permits and showed up at public hearings and tried to make compromises with bureaucrats, you may be left with the misconception that all opposition to the rally was the kind of militant activism that would make someone an irredeemable partisan unfit to stand in judgment of the opposition. The reality is less exciting - just ordinary people making do in an extraordinary circumstance.

In a 1943, Judge Jerome Frank wrote, "Impartiality is not gullibility. Disinterestedness does not mean child-like innocence." Having publicly professed to be personally opposed to racism does not preclude a prosecutor from trying a case involving a white supremacist rally any more than we would require a prosecutor with a neutral stance on pedophilia to try a case of child sex abuse. And despite Judge Padrick's explanation for his ruling in the courtroom, the message he's sent is far from the intended one. In his concern that an outside observer may see a biased court, he actually created the perception that his ruling was a result of those conspiracy theories being proved true in a court of law.

Jacob Dix's case was set to go to trial in February. Now that a special prosecutor will need to be appointed, it's unknown when the case might proceed to trial but it's unlikely we've seen the last of these theatrical courtroom performances and overwrought motions. With a victory like this under their belts, why shouldn't they feel vindicated in their strategy? Of course the pursuit of justice feels unfair to the torchbearer in the march toward fascism.