Burning Hate

There is no statute of limitations on felonies in Virginia.

With that in mind, here is Section 18.2-423.01-B of the Code of Virginia.

§ 18.2-423.01. Burning object on property of another or a highway or other public place with intent to intimidate; penalty.

A. Any person who, with the intent of intimidating any person or group of persons, burns an object on the private property of another without permission, is guilty of a Class 6 felony.

B. Any person who, with the intent of intimidating any person or group of persons, burns an object on a highway or other public place in a manner having a direct tendency to place another person in reasonable fear or apprehension of death or bodily injury is guilty of a Class 6 felony.

On August 11, 2017, hundreds of torch bearing marchers traversed the grounds of the University of Virginia. They'd come to Charlottesville from across the country, taking Friday morning flights or taking turns at the wheel for cross country drives in rented vans with guys they met on message boards, arriving early before the big event the following morning. They gathered at Nameless Field (a grassy acre near the UVA tennis courts with a deceptive name) and distributed tiki torches. Men with walkie talkies clipped to their belts, some with wired earpieces, barked orders. Elliott Kline, an ambitious young white nationalist organizer calling himself 'Eli Mosley' after 20th century British fascist Oswald Mosley, shouted at the crowd as they formed into a line, "We're pickin' big guys, no females!" Kline and his security team would be selecting the biggest marchers to lay down their torches and keep the perimeter as the march moved through the University grounds. They might need their hands free.

The march wound its way through grounds, up the lawn, then up the steps of the University of Virginia's iconic Rotunda. On the other side of the Rotunda, gathered near the statue of Thomas Jefferson, a small group of anti-racist activists waited. In her testimony during a later civil trial, one of the women who was terrorized that night said, "When we heard the roaring" of the approaching crowd, "we just linked armed and held hands and started to sing." She said at first it sounded "like thunder, like the earth was growling." As they grew closer, but before she could see the light of the torches, she began to make out the chants. Hundreds of voices raised in unison, shouting, "BLOOD AND SOIL." Testifying about that night four years later, she said she still heard it in her nightmares. And by the time the small group of mostly students realized the magnitude and ferocity of the approaching mob, it was too late - they were surrounded at the base of the statue by hundreds of torch wielding white supremacists.

For just a few minutes – minutes that those trapped at the base of the statue said they believed might be their last as they were doused in lighter fluid, maced, and punched – there was a melee. The police made no move to intervene as streams of pepper spray were let loose and screams of "Medic!" were audible above the roar of "You will not replace us!"

When the trapped counter protesters were finally able to flee, stumbling blindly with burning eyes and covering their heads in a hailstorm of fists and torches, the marchers declared victory. Richard Spencer, an organizer of that weekend's rally, climbed the base of the statue and delivered a victory speech to the still roaring crowd, now shouting HAIL VICTORY, HAIL SPENCER as Spencer told them, "We occupy this ground, we won!"

The marchers dispersed to their various hotels, campgrounds, and AirBnBs (Spencer claims he booked his under the pseudonym 'Literally Hitler'). They had to rest up for the real battle in the morning. While they slept, a young man from Ohio was driving through the night, perhaps already knowing his gray Dodge Challenger would be impounded as a murder weapon before he slept again. He checked Twitter and retweeted a post. David Duke had tweeted images of the torch march, celebrating the alt-right's success that evening, with the caption "Our people on the march. Will you be at #UniteTheRight tomorrow?"

Before he left Ohio that evening, his mother texted him "be careful." And James Alex Fields, in one of his last texts before a lifetime behind bars, replied to his mother with a photograph of Adolf Hitler and the words "We're not the ones who need to be careful."

Five and a half years later, the word "Charlottesville" has become synonymous with those two fused images - Fields' mangled Challenger and an iconic photo of the crowd, torches in hand, the Rotunda at their backs. Fields was convicted, both in state and federal court, of Heather Heyer's murder and multiple counts of aggravated malicious wounding. Daniel Borden, Alex Ramos, Jacob Goodwin, and Tyler Watkins went away for a brutal gang beating of a young Black man. Richard Preston, an Imperial Wizard in the Ku Klux Klan, did some time for discharging his firearm in the general direction of another young Black man after shouting "Die N-—r!" But all in all, for all the violence of both days, there was a curious reluctance to bring charges for anything that didn't rise to the level of attempted murder.

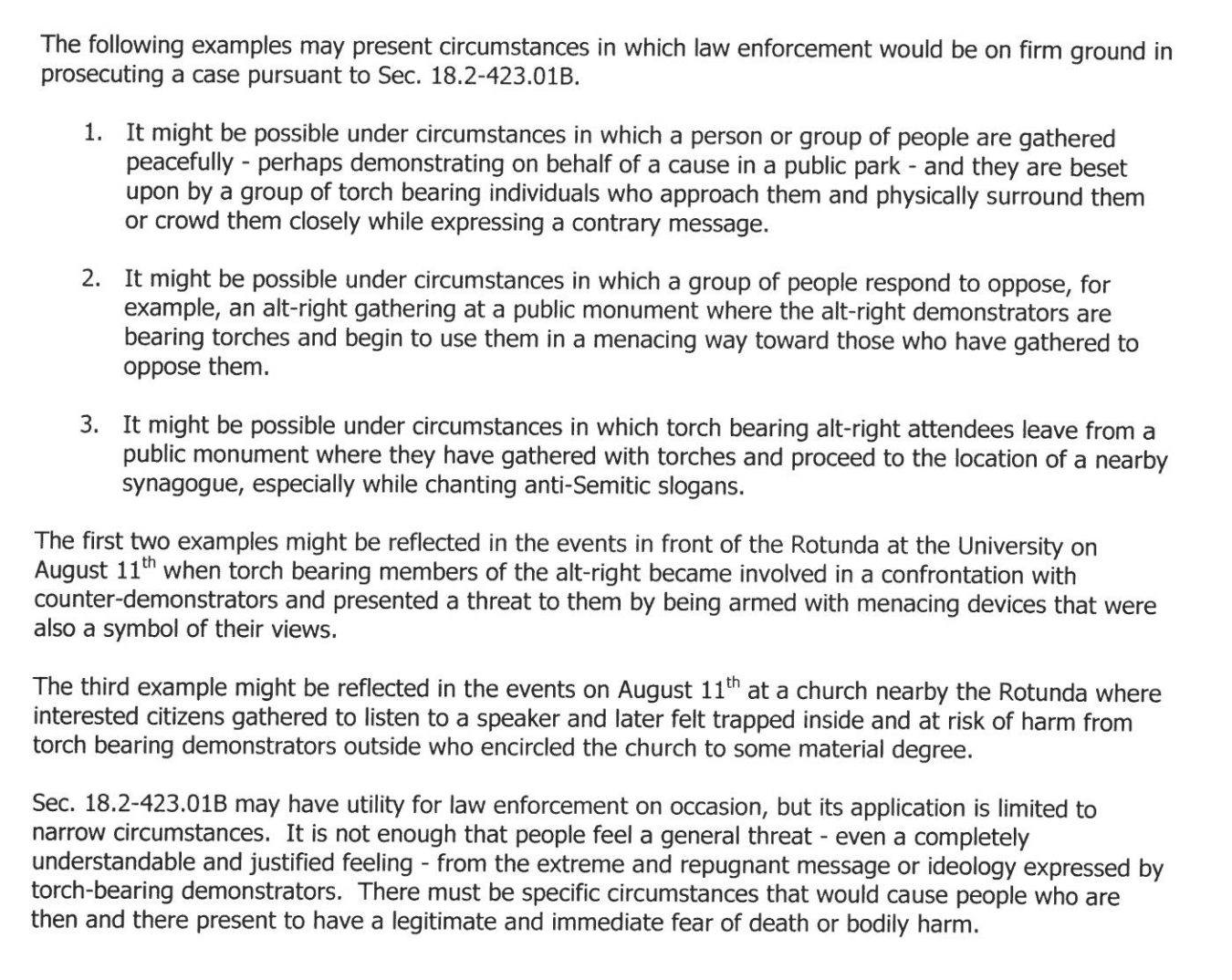

There are thousands of photographs, video from every conceivable angle taken by victims, bystanders, professional photojournalists, and even the marchers themselves. Their faces are uncovered. Their motives are clear. The law is fairly straightforward. But the University of Virginia lies within the jurisdiction of Albemarle County. In 2017, Albemarle County Commonwealth's Attorney Robert Tracci chose not to bring any burning objects cases under Section 18.2-423. He didn't think he could make a case against the tiki torch mob. The Commonwealth's Attorney for Charlottesville at the time, Dave Chapman, wrote in a memo in October of that year that he believed the cases could be made, but the UVA cases weren't his to prosecute.

But in Virginia, prosecutors come and go and a felony lives forever. In an October 2019 debate between then-sitting prosecutor Tracci and his challenger, Jim Hingeley, Tracci again scoffed at the idea of indicting these cases, saying Hingeley's belief that it was even possible was a sign he was inexperienced and wrong for the job. A month later, in November 2019, Hingeley won the election. Now it seems he's trying to make good on his campaign promise of proving Robert Tracci wrong.

In February 2023, the Albemarle County Commonwealth's Attorney's office quietly sought, and got, indictments under the burning objects statute. A grand jury agreed with Hingeley - there was probable cause to believe that objects had been burned with the intent to intimidate. Fugitive warrants were issued. Arrests were made by local police in far ranging jurisdictions. Now, nearly six years after that hot night in August, the extraditions are starting.

Over the coming days and weeks, I'll share with you the stories of the men who carried torches that night. Some of them are now facing felony charges in Albemarle County, others may come to share that fate. After the crowd dispersed that night, after the deadly rally the next morning, those men went home. Some started businesses. Some died. Some trafficked drugs, beat their wives and choked their girlfriends, went to grad school, went to prison, started families, ran for office, left the movement, tried to lead the movement, or just tried to disappear. There are as many stories as there were flames in the night, when their voices joined as one, shouting "JEWS WILL NOT REPLACE US," then going their separate ways, back to the communities they came from. And now some of them are on their way back here, this time against their will.

Author's note: These stories are ugly. There will be images of violence and audio of hateful language. There is a need to lay bare who these men are and what they are responsible for, but there is a duty not to choose the most sensational images for shock value, to allow ourselves to seek out the most extreme transgressions for the mere thrill of experiencing it vicariously, or to lift up and spread radicalizing propaganda. And there is a duty to the victims of this particular night of violence and to everyone who has lived in fear of what it symbolized - a duty to be honest for them, but not to exploit their pain. There is no clear line to walk between showing the truth of something vile and showing too much of it and in my work, I have strived to shine a light into the dark to drive out that darkness, not to put a spotlight on the monsters that lurk within it. But these are the stories of individual men, in individual moments, making the choices that ended in violence.

Take care of yourselves and each other, it's really all we have.