Becoming the Attorney for the Damned

When I started writing The Devil's Advocates, one of the themes I wanted to explore was the inadequacy of our legal system, rooted as it is in white supremacy, as a tool to bring white supremacist organizing to heel. The structures designed to ensnare people of color and people in poverty can, and do, sometimes catch those who yearn for an ethnostate the same way a hunter who fails to wear blaze orange may be mistaken for a deer. Sometimes it's friendly fire. Sometimes it's punishment for poaching, encroaching on the state's monopoly on violence. My vision for The Devil's Advocates is not just to tell the stories of successful prosecutions that stymied fascist violence, but to explore the many ways in which opposing forces attempt to weaponize the justice system. As a practicing attorney and criminal defendant, Augustus Sol Invictus finds himself at the center of both of those stories.

Earlier this year, Augustus Invictus updated his website, adding a new header at the top reading: "Augustus Invictus: Attorney for the Damned"

After earning his law license in 2012, renouncing it in 2013, coming back later that same year, announcing his retirement from law in 2017, and returning to practice in 2018, he was reinventing himself again. The site, ostensibly an advertisement for his legal services, is dominated by a gigantic screenshot of a Charlotte Observer article about his own acquittal on domestic violence charges. He proudly displays his own mugshot next to a professional headshot, juxtaposing the images to show potential clients that he's been where they are, he won, and you can, too. 'Attorney for the damned' is a mantle that's been claimed by several before him and applied to others. It's the title of two books about another Ohio-born attorney, Clarence Darrow. An attorney who provides state-appointed services to those deemed criminally insane wrote a book of that title about his career. There was an article about death row appeals in a 1987 issue of the American Bar Association Journal with the same title.

But perhaps the closest fit is another man who called himself the attorney for the damned, Edgar James Steele. Steele gave himself the nickname after unsuccessfully defending the Aryan Nations in a lawsuit filed by the Southern Poverty Law Center on behalf of a family who was shot at by security guards for the nazi compound in Idaho. Steele died in prison in 2014, three years into a fifty year sentence for (unsuccessfully) hiring a handyman to murder his wife with a pipe bomb. In an almost too perfect synchronicity, Steele wrote a 2002 amicus brief on behalf of the Council of Conservative Citizens in the Supreme Court case Commonwealth of Virginia v Black, challenging the constitutionality of Virginia's cross burning law. It was this Supreme Court decision that forced Virginia to rewrite that statute, shoring it up against First Amendment defenses by adding the requirement of 'intent to intimidate.' It is this revised statute under which Invictus now finds himself facing trial for his participation in the 2017 torch march at the University of Virginia.

When Augustus Invictus announced his campaign for US Senate in 2015, he said his motivation for entering politics was a vow of vengeance he made in 2006 when the Drug Enforcement Agency forced the closure of the pharmacy where he had been working as a pharmacy technician. In later campaign speeches, he railed against the government overreach of the raid, telling an audience at Stetson University that "nothing illegal was taking place" in the pharmacy. Invictus' war on the war on drugs was a constant refrain on the campaign trail, but any real details about the event that launched a college dropout and father of three on his path to become an attorney and politician failed to materialize. His vendetta against the DEA was quickly lost in campaign coverage focused on a paper he wrote in law school advocating for eugenics and his own admission that he'd slaughtered a goat and consumed its blood in a pagan ritual in 2013.

Invictus' description of the event, a DEA raid the week before Thanksgiving in 2006 on a Tampa pill-mill that filled prescriptions for pain pills written by doctors who never physically examined the patients and a business owner who returned to England rather than fight the DEA, does line up perfectly with the raids carried out on Medipharm-Rx in Tampa and Medcenter Pharmacy in Lakeland on November 16, 2006. Both pharmacies were owned by a British businessman named Michael J. Anderson, sometimes calling himself 'Lord Michael Boxted,' who is currently fighting extradition back to the United States on 2017 charges of defrauding TRICARE. And both pharmacies were operated by Robert "Fat Bob" Caddick, a former hospital CFO who pled guilty to bribery in 1997 for accepting $10,000 in exchange for loans from the hospital's coffers. As Invictus said in his speech at Stetson University nine years after the raid, the November 2006 event was purely an administrative action carried out by the Drug Enforcement Agency - no one was charged with a crime that day. They simply confiscated over half a million doses of hydrocodone and alprazolam and suspended the pharmacies' licenses to dispense controlled substances.

A few months before the raid, the DEA issued a show cause order for Medipharm-Rx, demanding an explanation for unusual activity at the pharmacy. A DEA review showed that Medipharm was filling prescriptions for hydrocodone at a rate of 150 times that of a typical Florida retail pharmacy, making them the largest dispenser of hydrocodone in the state of Florida and the third largest in the nation at the end of 2005. According to later depositions in the consolidated national prescription opiate litigation, Medipharm was dispensing so much hydrocodone, that DEA diversion investigators met with the manufacturer, McKesson, about these orders specifically on more than one occasion and even visited the pharmacy to interview employees months before the raid. Medipharm had also failed to make legally required notifications to the DEA about any controlled substances that were lost, stolen, or otherwise unaccounted for. Medipharm later reported over 40 incidents in which quantities of hydrocodone were "lost in transit," but was unable to produce specific details or police reports related to the losses.

In later retellings of this time in his life, Invictus described himself as "ill-tempered and unforgiving," "on drugs," and with no clear goals in life after being involuntarily separated from the military. His job at the pharmacy had allowed his growing family to move out of their small apartment and into a "home in a beautiful gated community," with "all the fine furniture and jewelry that anyone could ever want," and he was able to take his wife and their three young children on vacations to Chicago and Paris. The Florida Department of Health shows no records of a pharmacy technician license ever issued to Invictus under his chosen moniker or his birth name of Austin Gillespie, which may explain his lament that "no comparable job existed" for him after the pharmacy closed. Instead, he returned to the University of South Florida to finish his undergraduate degree.

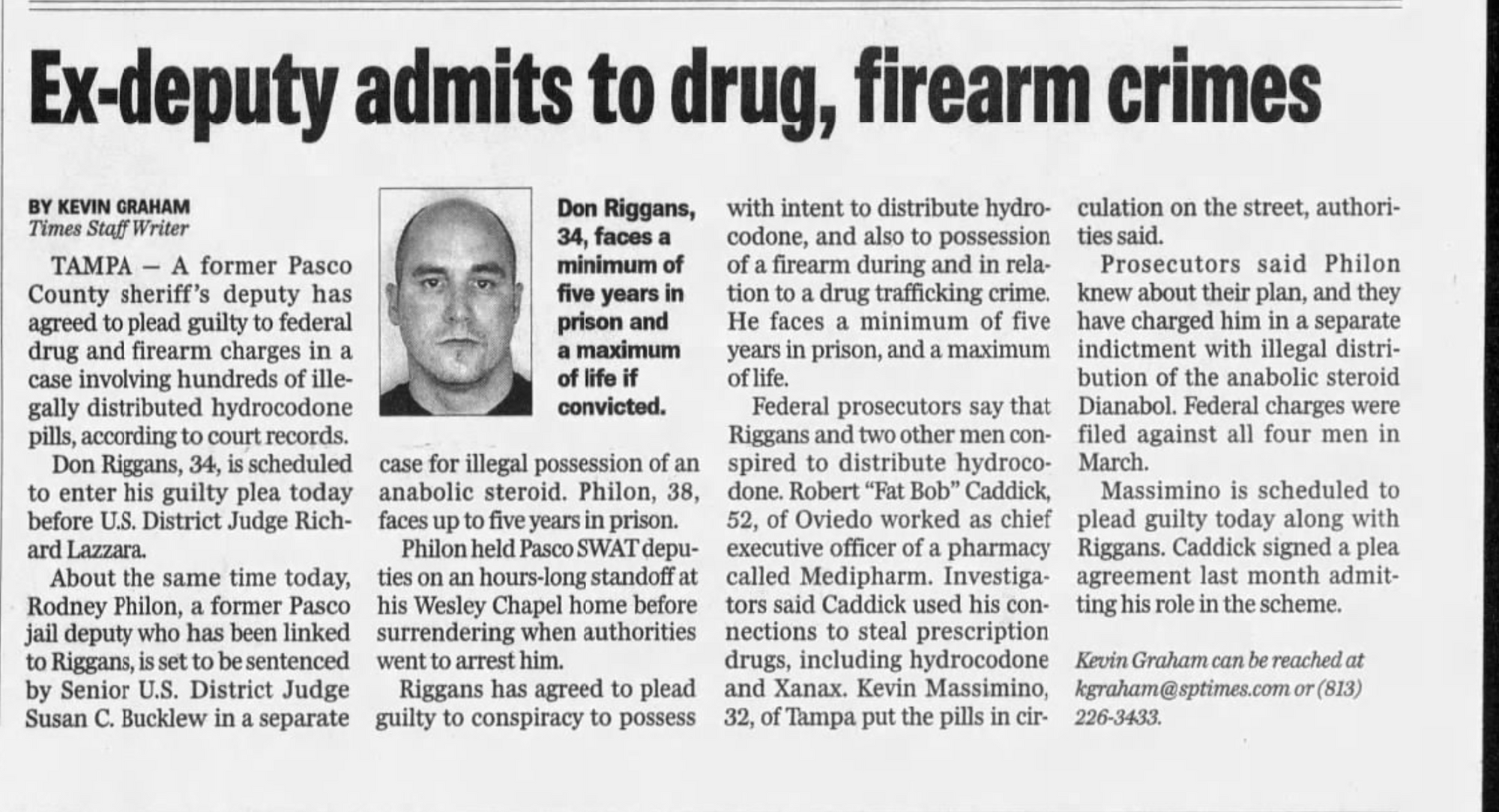

Later federal court documents outline Caddick's drug trafficking operation at Medipharm: cooked books to cover hundreds of thousands of missing pills that he funneled to Kevin Massimino to sell on the street; clandestine meetings in cars and parking lots and, on one occasion, the Hooters in Lakeland; staged thefts from the pharmacy's warehouse with the help of an inside man; and two Pasco County sheriff's deputies who helped them rob their own customers by staging traffic stops of couriers carrying tens of thousands of dollars in cash to exchange for the stolen pills. There is no mention in the documents of the pharmacy technician who lost his job somewhere along the way. By the time Medipharm-Rx CEO Robert Caddick pleaded guilty in December 2008 to conspiracy to distribute hydrocodone, Augustus Sol Invictus was enrolled in law school in Chicago.

Invictus graduated from DePaul University College of Law in 2011. As the Jeanne M. and Joseph P. Sullivan Human Rights Fellow, he co-authored a paper on human trafficking and sexual exploitation, perhaps coincidentally the same crimes for which his father now awaits trial. A law school paper he wrote advocating for eugenics resurfaced during his later U.S. Senate campaign, at which point he disavowed the paper, but not because his position on the paper's "underlying values" had changed, only that he had come to believe the government could not successfully implement the necessary measures. It was also towards the end of his time in law school that he began writing under the pseudonym Franco A. Saint-Fond. In July 2012, his novel Il Tempio Florido was published by a company called Pangenetor Corporation, which would be the publisher listed for several subsequent works through 2015, including a follow-up novel under the same pseudonym and three volumes of poetry under his legal name. Two iterations of Pangenetor Corporation have existed in Florida, one under Invictus' own name and one under the name of Brenden Caddick, Robert Caddick's younger son. At the time the novel was published, Pangenetor belonged to Brenden Caddick and Jason Gilkes, with John Gillespie of Acosta-Garcia, Gillespie & Young serving as the company's registered agent.

Upon passing the bar in both New York and Florida in 2012, Augustus Invictus filed for divorce from his first wife. In a financial affidavit, he indicated that he was employed at the law firm of Acosta-Garcia, Gillespie, & Young earning $2000 per month. The 'Gillespie' in Acosta-Garcia, Gillespie, & Young is John Gillespie, Augustus Invictus' father. Many of Invictus' early courtroom appearances were as co-counsel on his father's cases. Just weeks after being admitted to the Florida bar, Invictus entered appearances in two fairly high profile cases his father had been handling - Dustin Perry and Diane Stevens, two of the fourteen members of the white supremacist militia group American Front who were arrested on charges of engaging in paramilitary training at the group's compound outside of Orlando. The government alleged the group was training for a race war, relying heavily on information provided by a paid informant and the hope that defendants would turn on each other for plea deals. The cases fell apart in court and charges were dropped in ten of the cases, including the cases of Diane Stevens and Dustin Perry. Their charges were dropped just days after Invictus filed his notice of appearance, before he had a chance to attend a hearing or draft a motion in either case.

Perhaps Invictus felt disillusioned by his first few months as a practicing attorney. He wasn't at war with the DEA, he was handling his father's post-trial status hearings to ensure the court received paperwork that a client had completed traffic school. At the end of March 2013, Invictus moved to withdraw from a client's drug case, writing to the court that he was no longer employed by Acosta-Garcia Gillespie & Young. Three weeks later, on April 20, he wrote the infamous "Gray World of Man" letter, renouncing the practice of law and everything else in his life. The letter, received by some of his former law school classmates, was full of grandiose statements. He wrote that he was "of genius intellect" and "God's gift to humankind." He boasted of his "apartment downtown," his Cadillac and poodle, and his perfect pronunciation of words. But all of his accomplishments, travels, and possessions meant nothing to him. "This modern civilization of which you are all so fond deserves naught from me but the violence of my contempt," he wrote. The letter ended ominously -

HEAR YE MY FINAL WORDS IN PEACETIME:

I have prophesied for years that I was born for a Great War; that if I did not witness the coming of the Second American Civil War I would begin it myself. Mark well: That day is fast coming upon you. On the New Moon of May, I shall disappear into the Wilderness. I will return bearing Revolution, or I will not return at all.

War Be unto the Ends of the Earth,

Augustus Sol Invictus

The letter so deeply concerned many of its recipients that several people contacted the FBI. Invictus later said in a speech that the FBI called him to conduct a welfare check while he was away on this spiritual journey. Legal mail regarding a client whose case he abandoned without withdrawing from representing was returned undelivered. He had simply walked away from his life. The only accounts of what happened in May of 2013 come from Invictus himself. He wrote a self-published memoir of those events called The Black Pilgrimage, perhaps a reference to an experience written about decades earlier by a fellow Thelemite, Jack Parsons. In 1946, Parsons ventured into the Mojave Desert, as Invictus did in 2013. There, Parsons invoked the Thelemic goddess Babalon and later wrote of an out-of-body experience he called the Black Pilgrimage. In 1949, Parsons wrote The Book of Antichrist in which he described a second invocation of Babalon, revealing that the purpose of the Black Pilgrimage was to manifest the Antichrist. Modern Thelemic writings about Parsons' Black Pilgrimage do exist, but often with a more metaphorical understanding of the work. Most manuscripts actually advising aspirants to undertake a ritual by that name are produced by adherents of the Order of Nine Angles, a hermetic order of neo-nazi satanists who advocate for terrorism to bring about a new social order they call the "Imperium."

Upon his return from the wilderness, according to occultist Marco Visconti, Invictus mailed a copy of his memoir and a letter declaring himself "the successor of Aleister Crowley, a second Prophet of Thelema, here to purge by fire those of you who would call yourselves Thelemites," to the Master of every Ordo Templi Orientis lodge and temple in the world. In November of 2013, he was expelled from the organization for reasons that have never been disclosed. And, despite his renunciation of the practice of law just months earlier, he resumed practicing law. In July 2013, he entered an appearance on a probation violation case for one of the American Front members who had been convicted the previous year. When he filed notice in Osceola County court that he was representing Luke Leger, his signature line no longer read Acosta-Garcia, Gillespie & Young. Augustus Sol Invictus was now practicing law at his own firm, Imperium, P.A.

It was likely through his brief appearance in the cases of Diane Stevens and Dustin Perry in 2012 and his work on Luke Leger's probation violation in 2013 that Invictus met Marcus Faella. Faella, American Front's leader and the owner of the compound where the paramilitary activity occurred, was convicted on two felony counts in September of 2014. He was sentenced to six months behind bars, followed by two years of electronic monitoring. Invictus entered the case on appeal, filing his appearance on Faella's behalf in November of 2014. And while his representation of Faella certainly garnered him significant attention and appears in countless descriptions of his legal career, what's often omitted is that Faella's sentence was increased on appeal, with the judge adding an additional year of GPS monitored home confinement. Faella may have been Invictus' first real movement client, but after his brief 'retirement' to focus on trying to become a leading voice on the extreme right, Augustus Invictus would return to the practice of law to serve as a movement lawyer.